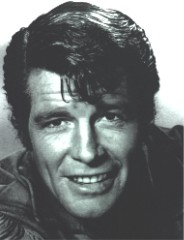

Flint McCullough

|

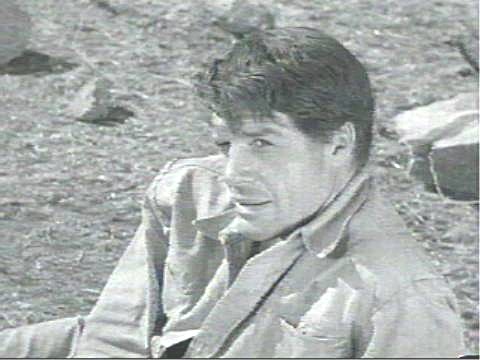

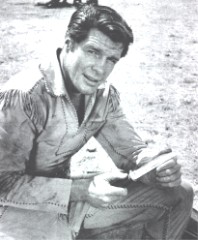

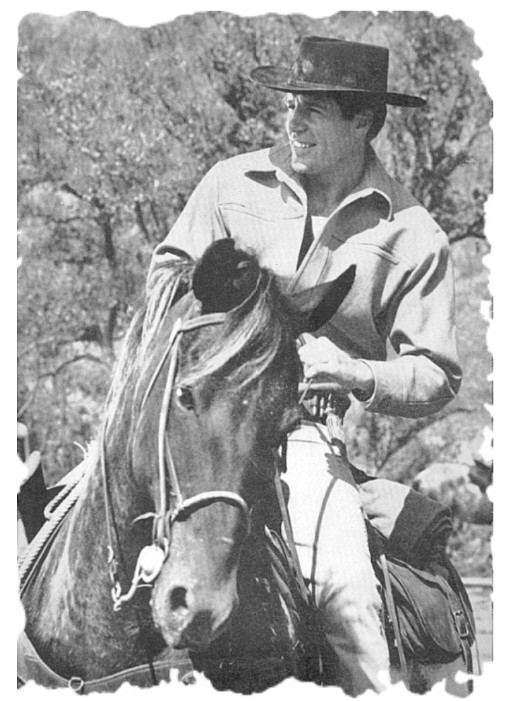

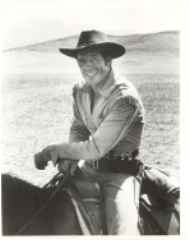

Robert Horton’s role as the intrepid scout, Flint McCullough, on “Wagon Train” is probably his most well remembered, and loved, role. That he made this character so real for us is a tribute to his ability, determination and thoroughness as an actor. One of the first things Mr. Horton did upon getting the role was to drive across the country from Missouri to California, to follow as closely as was possible the actual route taken by the pioneers on the wagon trains. He also wrote a “biography” for Flint, to keep the character consistent for all the various script writers and directors, and he has been kind enough to share that biography with us. The following background for “Flint,” was in Mr. Horton’s own words, “Based on the 'Jean LeBec Story,' and what I have said, or has been said about me so far in the series. It is historically accurate, and, if now and then improbable, still within the range of possibility.” |

||

|

|

|

|

Flint McCullough Biography By Robert Horton Flint was born in 1839 in Virginia, the son of a middle class family. His mother was a native of Virginia, his father an immigrant from Scotland who earned his living as a teacher at Virginia’s College of William and Mary. By selecting the teaching profession as his father’s occupation, and by choosing Virginia as his mother’s home, I feel that both a certain grace in his everyday living habits can (easily) be explained, as the old South was certainly the home of graciousness in early America, and also his early contact with education would not be too difficult to understand. In 1850 his family moved from Virginia and headed west for Salt Lake City. I chose this year, as this was the year the University of Utah was founded. This would give a logical reason for the move from the father’s standpoint economically, and if you chose to have him interested or converted to the Mormon faith you would only double the motivation. This would also give young “Flint,” now eleven, his first contact with the problems of crossing the plains, acquaint him with the Oregon Trail as far as the South Pass, and then through the pass to Fort Bridger, and on to Salt Lake. As you know, this route was the route of the Donner Party, the Mormons, and a great majority of those pushing on to California. While at Fort Bridger, where the wagon trains were accustomed to stopping for repairs and supplies, “Flint” meets Jim Bridger. By 1850 Bridger was already a legend and had been spoken of most generously in Fremont’s book, published in 1842, “Reports on Expeditions Exploring the Rocky Mountains.” It stands to reason that a person who could read and who planned to make the trek west would certainly have read this book sometime within the eight years after it was published, especially in an academic environment. Therefore, Flint knows about Bridger, and can have a kind of hero worship for the scout, and Bridger, who took up the study of Shakespeare when he was in his later years, could be flattered and more than casually interested in a young boy who could read, and had read about him. This friendship can be developed in imagination, as Bridger often went through Salt Lake City. In the winter of 1852 the Mormons had a particularly bad cold season, and during this winter, in my story, I choose to have Flint’s father pass away with pneumonia. This I feel would aid in Flint’s maturation, as now he, in essence, would be the head of the family. This would also serve in motivating an even closer relationship between him and Jim Bridger, the later becoming a kind of father. This relationship now opens up and explains Flint’s understanding of Indians. The Mormon people were on friendly terms with the Ute tribe, and this tribe spoke a dialect of the Siouan language, one of the great linguistic families of the North American Indians, engulfing nearly all the tribes who lived between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Add to this the fact that Bridger had two wives, both squaws, picturesquely named, Blast Your Hide, a Cheyenne, and Dang Your Eyes, an Arapahoe, and you further explain Flint’s understanding and acceptance of Indians and their customs, and as he was Jim Bridger’s friend, the Indians accepted him. Bridger was celebrated across the frontier as a scout, trapper, hunter, and fur trader, and by linking Flint’s life with his, from 1850 through 1857, the how in my characterization of Flint can be gradually explained. To continue, in 1855 Bridger returned East, and ultimately was hired as a scout by General Albert Sydney Johnston. In my story Flint goes with him, crosses the plains for the second time, and with the advent of the Civil War why shouldn’t Flint cast his lot with the South. After all, his mother was from Virginia. At the end of the Civil War, with the South in ruin, Flint returns to the thing he knows best: the frontier. The last I heard of him, he was scouting for Major Seth Adams. |

||